HURLING, GAME OF LEGEND AND OF LEGENDS

by Tom Kenny

Hurling is one of the oldest field games in the world. Some stories portray it as a form of military training, proficiency on the field equated with skill in battle. Legend has it that the first battle of Moytura fought about 2000 B.C. between two rival tribes, was preceded by a fierce hurling match between two teams of 27 a-side drawn from opposing forces. The casualties were buried under a huge stone cairn – a megalithic tomb. The field where the game took place is still called The Field of the Hurlers. Ancient games were also played at Tara.

Lowry Loingseach, the legendary pagan king with the ass’s ears was suddenly cured of deafness when accidentally struck by a hurl in a hurling contest. Setanta was a warrior hero and a demigod whose feats on the hurling field are legendary, he killed the savage hound of Culainn in self-defence and thereafter was known as Cú Chulainn. Fionn Mac Cumhaill and the Fianna played hurling. Some kings left up to 50 hurleys and hurling balls in their wills so that their sons and warriors would carry on the noble game. The earliest written reference to the game was in the 5th century Brehon Laws. Hurling was outlawed in the 12th century by the Normans and later a bishop threatened to excommunicate any Catholic who played the “reprehensible game of hurling since it led to mortal sins, beatings and homicides”.

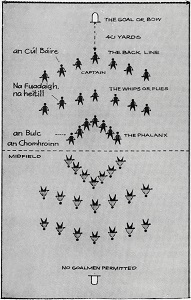

Early hurling was played over a wide area, from field to field as it were, until one team was ‘beaten home’. As time went on, the idea of playing it in one particular place, or field, developed. The fence at either end was the goalpost and whoever hurled the ball over the fence scored a goal. The ball was large and heavy and there was no such thing as picking it off the ground. The game might be played by teams of 50 a-side and lasted many hours. It was not until the 18th century that the notion of goalposts came to pass and it was then in the form of an arch, two sally rods sunk in the ground and joined overhead to form an archway as you can see in our illustration. These were the normal goalposts in Co. Galway for more than 50 years.

In the real old style, goalposts were 400 yards apart and 15 yards wide with 25 players a side. There were no side lines and any hurler who lifted the ball had to fall out. After the matches there were usually entertainments, Irish music, dancing and socialising into the small hours, all of which helped to make the game close to the hearts of the people.

A report in the Morning Chronicle of 26th of October, 1773 tells us that “a grand hurling match between the County of Galway and the County of Tipperary, for 1,000 guineas, was finally decided in favour of the latter, near Banagher. There never, perhaps, was so great a company seen in this kingdom before, as, at the lowest computation, there could not be less than 10,000 persons present”.

The Famine changed everything for the nation and for the game, but there were areas in the country that were not as badly affected as others such as East Galway and North Tipperary between whom there was great hurling rivalry and where the game continued to be played. It was from these areas that the idea of a national association for Gaelic Games was to come. Michael Cusack was for a time principal of Lough Cutra National School near Gort and he organised a meeting in Sweeney’s house in Loughrea on August 15th, 1884. They asked their bishop to be patron of their proposed organisation but he said he was too old and suggested the 'young' Dr. Croke, Archbishop of Cashel and so on November 1st, 1884, the Gaelic Athletic Association was formed in Thurles.

The first published rules of hurling were designed in Killimor. Up to then, the hurling ball was made up of pressed paper or cow’s hair, a little lead, it was covered with leather and was very heavy and dead in wet conditions. On August 27th, 1887 a number of men were in Fitzpatrick's pub in Killimor discussing the problems with the ball. There was a whiskey bottle on the table with a cork in it and one of the men suddenly thought – if bottle corks were tied together, wound with twine and covered with leather, a ball of the right size and weight could be found. The local saddler was called in and they experimented with corks, twine, leather and an odd drink until they had a ball of about 4 inches, light with a perfect bounce, that should not take water. This ball was used in the first All-Ireland final which took place in Birr on April 1st, 1888 between Galway (Meelick-Killimor) and Tipperary (Thurles Sarsfields) which the Thurles team won.

Our illustration shows that, contrary to common belief, in the 18th century hurling teams used to line out in a pre-determined, highly organised manner, subject to strict rules. The captain stood forty yards in front of the goal flanked by three men and was forbidden to stand nearer the goal unless the ball went closer than he. The pitch was 200-300 yards long and no end lines were marked. The Frenchman Coquebert de Montbret described the formation as follows in 1791: “Each team is divided into 3 divisions – L’arriére or ‘back’ guards the goal and seeks to stop the ball from passing through; another group is in front to prevent the enemy’s ball from coming back from that end, that is the middle; the third, called ‘the whip’ is sur le terrain. The sides are distinguished by the colour of their caps. It is terrifying to see the way they rush against each other to force the ball to pass under the goal”.

Most of the above, including the illustration, comes from an old pamphlet entitled “The First All-Ireland Hurling Final Centenary, 1888-1988” written by Padraig Rooney and published by Meelick-Eyrecourt GAA Club. Some material is from a recent pamphlet titled “Eighteenth Century Hurling” by Steve Dolan, one of an impressive series of pamphlets on Galway Gaelic Games currently available and highly recommended.