Old Galway

“YOU WOULDN’T HAPPEN TO BE WILLIAM JOYCE, WOULD YOU?”

by Tom Kenny

William Joyce was born in Herkimer Street, Brooklyn, New York in 1906 to Gertrude (who was originally from Lancashire) and Michael Joyce, a native of Killour, Co. Mayo. Michael had taken American citizenship, which automatically made his family citizens. In 1909, the family returned to Ireland, initially to Mayo, then to Galway.

They lived at Ruttledge Terrace in Salthill. William attended the Mercy National School and later the Jes, where ‘the staff and the students were rough’. But he was always grateful for the sense of discipline and a love of language they instilled in him. His best subjects were Latin, French, German and English poetry. He enjoyed the rough and tumble of the playground and had his nose broken in a fight which left him with a nasal tone of voice. He was a bombast, precocious and a gang leader.

CLARE SHERIDAN

by Tom Kenny

“She was beautiful, fearsome, an English aristocrat, a communist spy, a loose woman, a middling novelist, a doting mother, an impossible parent, a successful sculptress, a respected journalist”. This was how Anita Leslie described her first cousin in “My Cousin Clare”, her wonderful biography of Clare Sheridan.

Clare was born in London in 1885. Her father was Moreton Frewen who was known as ‘mortal ruin’ for his extraordinary capacity to fritter away the family fortune. Her mother was one of the fabulous Jerome sisters who dazzled London’s Edwardian society with their beauty and style. She was educated at home by governesses and later at a convent school in Paris. She was a debutante at 17 but turned away from that social scene. She married William Sheridan, a descendant of Richard Brinsley Sheridan. They had three children, one of whom died. Her husband was killed in World War 1.

While mourning her child, she was encouraged to make some kind of memorial so she worked on a model of a weeping angel for her daughter’s grave. She realised she had ability as a sculptor and took up the art form as a career. She was commissioned to sculpt heads of well-known people and held a successful exhibition. As a result she was invited to Russia and against the wishes of her cousin Winston Churchill, she went and stayed for two months. While there she made portraits of a number of eminent Russians including Lenin and Trotsky, and apparently had affairs with some of her sitters. When she returned to London she was shunned and so left for America.

COMPETITIVE ROWING IN GALWAY

by Tom Kenny

Rowing ‘matches’ or ‘badge races’ have been taking place on the Corrib for about 170 years. Initially, when there was only one club, The Corrib Rowing and Yachting Club, competitions were confined to members. Then the Commercial Boat club was formed in 1875, and a meeting was held to promote a regatta at the river beside Menlo Castle. This regatta proved to be a success and was a great boost to the sport of rowing.

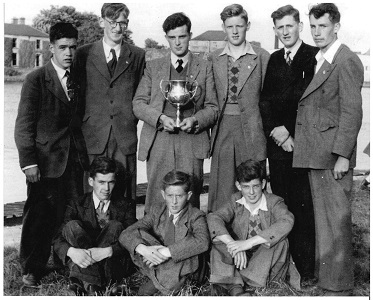

It was decided that the regatta should be independent of both clubs and should encourage friendly rivalry and competition. It quickly became an important annual event. Soon, other clubs were formed. St. Patrick’s Club aka The Temperance club was followed by the Royal Galway Yacht Club; Hibernian Rowing Club aka Galway Rowing Club; Galway Athletic Rowing Club; The Citie of the Tribes Rowing Club and Emmett’s Rowing Club. Later, U.C.G. set up a club as did Coláiste Iognáid and St. Joseph’s College. The rivalry between these two powerful school rowing nurseries meant standards in the sport in Galway would always be high.

THE TURF MARKET

by Tom Kenny

James Hardiman, in his history of Galway lists the fuels available in Galway long ago as coal, turf and bog deal. Bog deal was mostly the roots of trees that had been grown over by the bog over the centuries. It was regarded as a nuisance by the turf cutter who likes nice clean lines as he used his sleán. The turf men usually threw this timber up on top of the bog. It gave out a lot of sparkle, like a mini fireworks, while it burned in the grate.

Coal was imported. The main fuel for firing was the most accessible, turf. Some of this was also ‘imported’ to Galway in the sense that boat loads of turf from Conamara would arrive daily at the docks. This turf was bought as soon as it was cut by boatmen from the Aran Islands and Clare. They usually paid the turf cutters one shilling and one penny per ton. Then, they would bring it in to Galway to sell for about a guinea (one pound and one shilling) per four-ton boatload.

ALTAR BOYS IN THE ABBEY

by Tom Kenny

An altar boy is a lay assistant to a member of the clergy during a Christian liturgy.

‘Ad Deum qui laetificat juventutum meum’ was the first of many Latin responses altar boys had to learn to answer the priest. You might not have a clue what the words meant but you needed to know to put them in the right sequence. You had to get up earlier in the morning than your mates, have your clothes hands and face clean, your hair combed, your shoes polished, know when to ring bells, how to light candles, how to separate all the chains on the thurible and do all of this with grace and dignity. Above all, you had to remain attentive throughout mass, if you allowed your mind to drift, some of your responses might come out in a language of unknown origin.

THE GALWAY & CORRIB ANGLER’S ASSOCIATION, THE EARLY YEARS

by Tom Kenny

On February 6th, 1898, Colonel O’Hara from Lenaboy Castle and Henry Hodgson from Currerevagh, Oughterard came together to found The Corrib Fisheries Association for the further improvement of trout fishing on the Corrib. They teamed up with the Board of Conservators of the Galway District to promote proper angling on the Corrib. In 1907, they managed to convince the Department of Agriculture to build a trout hatchery on the Owenriff River in Oughterard. It worked very well for a number of years but eventually fell into decline and closed down in 1924.

As a result, the sport of trout angling on the lake was deteriorating and so a number of concerned anglers met in Bailey’s Hotel and set up The Galway and Corrib Angler’s Association with Mr. L. O’Dea as chairman. Their stated aim was to improve angling on the Corrib and to investigate and report to the Government Commission on inland fisheries in the country. As members of the association, they were allowed to participate in the National Fly Fishing Competition to be held on the lake in April of that year.

M.J. Lydon was elected secretary, Nicholas Geraghty became treasurer and the committee members were Lieutenant Graham, Renmore, Dr. D.V. Morris, G.M. Counahan, Ed. Bailey, E. Lydon, Michael Power, William Cloherty, J.M. Pringle, T. Sweeney, F. Ryan, T. Courtney, J. Moloney and H. Bailey.

They set about trying to re-establish the trout hatchery at Oughterard and they organised fishing competitions, some of which were specifically for pike which was an attempt to control trout predation in the lake.

Thus began a long programme of outstanding work done by the Association over the years in preserving the quality of angling; in lobbying Government on various issues; in organising national championships; in protecting the ecology; in the distribution of fry; in monitoring pollution; in running fly-tying courses; in dealing with the rod licence; in highlighting bad lakeside developments and in building an angler’s hut on Flynn Island. They also worked valiantly and voluntarily to maintain the hatching facility at Oughterard but it was beyond the means of one angling club and so, in 1959, they were happy to hand over the running of it to the Connacht Federation.

In 1971, all the fingerling trout raised at the hatchery were lost due to drainage work. Pollution was increasingly becoming a problem, that same year all the fish in the Claregalway River were wiped out from a disastrous spillage from the Erin Foods factory in Tuam. The dreaded algae bloom was now being reported as a serious threat and later, fish farming for the same reason.

On the positive side, the Association teamed up with Bráithreacht na Coiribe, the other city based angling club, to run a fly-tying course in the Vocational school. In 1988, the club began their protest against the rod licence. They set up a special task force to fight it and organised a public march in the city. Eventually, the dispute was resolved.

Our first photograph shows some of the anglers in the 1952 pike competition including Archie Mahony with the pike on the left. Bernie O’Grady with the rod, Eamonn Walsh and Tommy Mannion with the large pike between them and on the right, Jack Doherty with his cap in his hand.

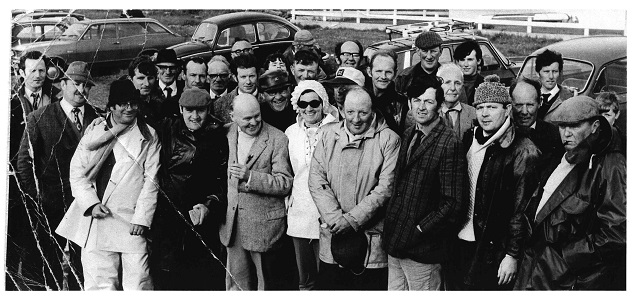

Our second image shows a group taken at Greenfields in 1971. In front are, from the left; P.J. Dowling, Galway; Murt Folan, Galway; Percy Stanley, Clifden; Eileen Brett, Tuam; J.J. Duffy, Kilmaine; Peter O’Malley, Ballinrobe; Tom Browne, Galway; Christy Deacy, Galway. Among those at the back are Pat Day, Mike Egan, Sonny O’Donnell, Jim Ryan, Tom Cameron, Bertie O’Toole, Tom Varley, Liam Greaney and Paddy Brett.

These photographs and all the information today is taken from a history entitled “Galway & Corrib Anglers’ Association, 75 Years” which was written and published by the late Peadar O’Dowd in 2009.

----------------------------------

Just arrived is a copy of the Galway Archaeological and Historical Society journal, Volume 76 edited by Dr. Jackie Uí Chionnaith. It is, as expected, a mixture of fascinating articles on a variety of subjects and is well illustrated. Of particular interest is Roy Foster’s piece on “The memoir of Dermot O’Connor Donelan” and also Séamua Devitt’s article on “The story of ‘The Irish Madonna’. This recalls how Walter Lynch, the Bishop of Clonfert along with many others fled to Inishbofin as the Cromwellians were about to take over Galway. When the island surrendered to the British, all of the clergy were allowed to leave and sail to Flanders. Lynch ended up in Gyor in Hungary with his most prized possession, a portrait of The Blessed Virgin. When he died, this portrait was hung in the local cathedral, and 37 years later, on St. Patrick’s Day 1697, it was seen to weep tears of blood for some three hours. ‘The Madonna of Galway’ painting was venerated thereafter. The article gives us the statements of those who witnessed the event. The journal also includes a wonderful tribute by Bernard O’Hara to Peadar O’Dowd who was an active member of the Society for many years.

Membership of this society is only 20 euro per annum and includes a copy of the journal and postage. Overseas membership is only 30 euro which also included a copy of the journal and postage. The society also host a series of lectures every year which are free to members. This represents remarkably good value to anyone who wishes to join this organisation who have made such an important contribution to our understanding and appreciation of our heritage.

THE CHANGING OF THE GUARD

by Tom Kenny

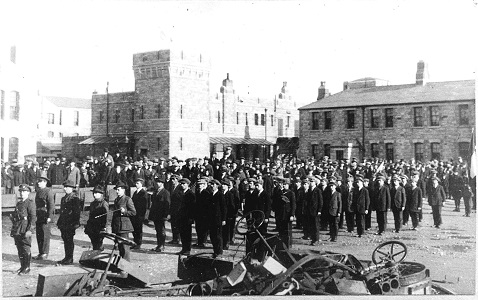

On this day, February 13th, 1922, the I.R.A. took over Renmore Barracks from the British. When the Anglo-Irish Treaty was ratified on January 7th 1922 ,it was only a matter of time before the British Army would leave the Barracks. There was some suggestion initially that the regional Hospital might transfer to the barracks. On February 2nd, the last Black and Tans had left Galway by train. The British did not want to surrender the Barracks to the Volunteers, so an arrangement was made where they would leave at a certain time, and the formal handover wold take place a few hours later.

The Irish officer assigned for the take-over was Captain Stephen Rynne formerly of the Dublin Brigade of the I.R.A. By the time he entered the premises, the locals had stripped the barracks of most of the furniture. Two Volunteers, John Murphy and Sonny King raised a large tricolour. An advance guard arrived to replace the military sentries and are seen in our first photograph. They are, from the left, Henry Lynch, John Bannigan, John Canavan, Patrick White, Michael Francis, Joseph Kelly, Patrick Feeney and Sergeant Thomas Kelly.

GRATTAN ROAD BUILDINGS

by Tom Kenny

The Galway Vindicator of November 24th, 1863 reported that “The completion of the Grattan Road will add much to the beauty and salubrity of the handsomest of our suburban districts. The embankment being made by Miss Grattan will reclaim 28 acres of land, which is now a swamp, but which will become, with a little cultivation, some of the most fertile ground in the neighbourhood. Miss Grattan has given great employment to the poor of the neighbourhood in making this road and embankment. Since June last, up to the present time, there has been over 200 labourers employed and from 12 to 14 masons regularly. It will, when finished, alter the appearance of Salthill and contribute much to make that favourite watering place one of the nicest localities in the kingdom”.

Miss Grattan was a relation of Henry Grattan. The project was known as ‘The Tenpenny Road’ as that was the weekly wage paid to the labourers. It was a major factor in the improvement of Salthill, indeed it was the first time land was reclaimed in the area.