Old Galway

THE CHRISTMAS MARKET

by Tom Kenny

The Saturday Market at St. Nicholas’ Collegiate Church is a Galway tradition that goes back some 800 years. It was a fruit and vegetable market which expanded greatly at this time of the year when the farmers brought in large numbers of turkeys and geese for sale.

From very early morning, a procession of donkeys would set out, nose to tail, for the market. There, the donkeys were unharnessed and tethered to a wheel, the shafts were let down and the goods to be sold were displayed on the sloping cart. Vendors came from many more prosperous areas and their wares were a source of envy to those who lived in the congested strip along the coast. Eggs in big wicker baskets with hinged lids, ducks, hens and chickens, wooden kegs of buttermilk, home-churned butter laid in rolls on cabbage leaves, cabbages, onions, sometimes geese, hand-knitted socks --- all sold briskly to people of the town. At Christmas time, this market would be much bigger than normal and there might be two or three extra market days where the emphasis would be on selling turkeys or geese. On these days, the activity would extend into adjoining streets.

TOWN HALL INTERNMENT CAMP

by Tom Kenny

The last months of 1920 were the most vicious and bloody in the war of Independence in Galway. There were a lot of killings, burnings, shootings and beatings. There was a sweeping roundup of hundreds of the usual suspects and the old gaol in Galway could not take any more prisoners. Two internment camps were opened in the city, one in the military camp on Earl’s Island where “33 of us were given 32 blankets and herded into an old hut without glass in the only window, and never got a cup, knife or cup during our 13 days” according to John Costello. These prisoners were eventually moved into the Town Hall Theatre which was commandeered as the second internment camp.

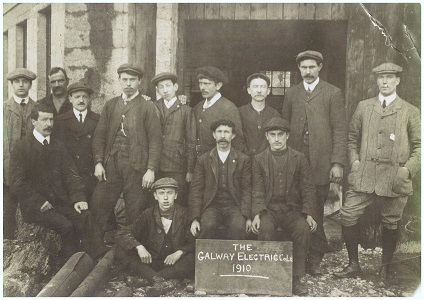

THE GALWAY ELECTRIC LIGHT COMPANY

by Tom Kenny

The Galway Electric Light Company was set up by James Perry, an engineer and County Surveyor of the Western District of Galway, and his brother, Professor John Perry to generate electricity. On November 1st, 1888, they applied for permission from the Galway Town Commissioners to ‘erect poles in some parts of the town as an experiment for the electric lighting of the town’. The company had established a generating station at Newtownsmith in an old flour mill which had existed since the 1600s and straddled the Friar’s River. They installed a hydroelectric turbine in the watercourse which was linked to a generator producing alternating current.

The plant at Newtownsmith consisted of a 200 BHP VJ4 Vickpet crude oil engine manufactured by Vickers Petters of Ipswich, a National and Crossley gas engine of 60/70 BHP each fuelled by anthracite coal and a Hay Maryon turbine of 130 HP supplied by water power. In addition, they had an extensive battery system where surplus current could be stored. The company started off with a private scheme customer base of 59 houses and this was the reason for their application to erect poles to deliver current to their customers.

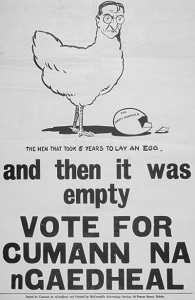

SOME OLD ELECTION POSTERS

by Tom Kenny

Election posters are very much part of the democratic process. They are primarily used to urge people to vote, to communicate political messages, rally public support for a candidate or a cause. They play an important role in our documentary history and are often a powerful way to capture a moment in time. They can be used to educate, inform and inspire people. They also generate loyalty to the cause from the thousands of volunteers who hang the posters up. They were an especially powerful form of communications for previous generations.

In the latter part of the 19th century a kind of ‘cartoon war’ developed between Ireland and the UK. The British cartoonists increasingly caricatured the Irish as simian, ape-like creatures, ogres. The Irish cartoonists, on the other hand portrayed the Englishman as a normal man, a portly tweedy John Bull. But the Irish used the word as the strong weapon to get their message across. These continued into the early 1900s as political posters were used to promote the cause of Irish Independence, often in a highly emotive way depicting powerful images of the Irish people and their struggle for freedom.

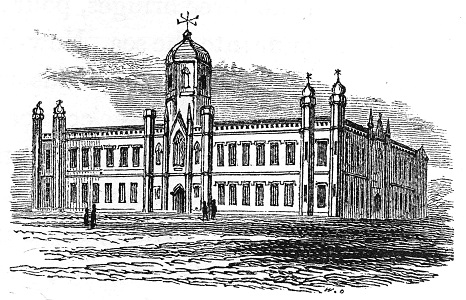

QUEEN’S COLLEGE, GALWAY, THE EARLY DAYS

by Tom Kenny

The Queen’s Colleges in Galway Cork and Belfast were established in 1845, and shortly afterwards, construction of the quadrangular building started in Galway. In May, 1847, despite the Famine, William Brady, the contractor for the building, advertised for thirty stone cutters and thirty stonemasons. Large working sheds were erected on the site so that the work could be carried out in inclement weather. There was no big rush to work from the stone men as the money he offered was below the going rate, but as it was a long term job with shelter provided, so it had a security of employment not available on other building projects. In the end, the building of the College did have a beneficial effect on the depressed conditions in Galway at the time.

The first students walked in the gate in October 1849, 175 years ago. The Colleges had been denounced as ‘godless’ by the Catholic hierarchy so Galway had, from the beginning, difficulty in attracting students. But, by 1859, 18 of the 31 students who sat the matriculation exams here were Catholics. There were eleven entrants for arts, twelve for medicine, one for law, three for engineering and four for agriculture.

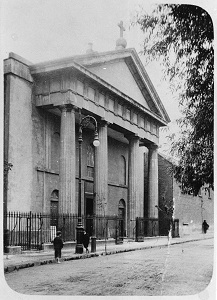

THE FRANCISCANS IN GALWAY

by Tom Kenny

In the graveyard at the back of the Abbey Church in Francis Street stands an interesting memorial carrying the De Burgo coat of Arms and a long broadsword. The inscription tells us that it was erected in memory of William De Burgo who founded the Franciscan friary on St. Stephen’s Island in 1296. The site was roughly where the Courthouse is today and the island was formed by the Galway River on one side and a branch of that river which ran through what today would be Woodquay and Mary Street and re-joined the main river. A second and smaller island lay between St. Stephen’s and the town wall, so that in order to maintain communications with the town, two bridges were necessary, one at the junction of Mary Street and Abbeygate Street and the other at the Little Gate. The Abbey buildings lay immediately north of the present graveyard and between them and the river was ‘Sruthán na mBráthair’, a small stream that enabled the friars to bring boats in from the main river. The monastery was known as the Abbey of St. Francis.

DEVELOPMENTS IN THE CLADDAGH

by Tom Kenny

Towards the end of the nineteenth century, the Claddagh started to go into decline, thanks mainly to the local fishermen not updating their methods of fishing. This economic decline continued into the last century so, when the Urban District Council announced in 1916 that they were starting a reclamation programme of the 30-acre field that was known locally as ‘The Swamp’, it caused a lot of excitement locally. A small working committee was established to carry out the details of organisation. From then on the area was to be known as South Park. I am not sure where that title came from, maybe they regarded the Square as East Park, Salthill Park as Westpark, but where was North Park?

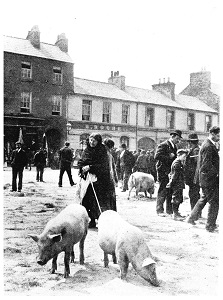

FAIRS AND MARKETS IN THE SQUARE

by Tom Kenny

In 1902, the number of fairs listed for Eyre Square was; January 1st; March 20th & 21st; April 14th & 15th; May 30th & 31st; June 20th; July 13th & 14th; August 6th; September 3rd& 4th, 20th & 21st; October 21st; November 2nd (pigs only); December 8th & 9th. This list gives one an idea of how important and busy the Square was for commerce at the time. These were occasions when the country came to town, when rural people brought in their produce and hoped to convert it into cash.

There was a variety of fairs, cattle, sheep, pigs, horses, hay markets, turf markets, sock markets, egg and butter markets, potato markets and sadly, the hiring fair. This last one was the worst one of all and dealt in humans, spailpíns, out-of-work labourers, usually from west of the city who would gather at the railings opposite the Skeff and hope they might be hired by farmers who usually came from east of the city, or oyster growers from Clarinbridge. There cannot have been much dignity attached to that fair.

.png)